Greening Barnet’s existing homes

My web post on 25 September about the crucial importance of minimising carbon emissions from Barnet’s existing housing stock looked at the challenge of upgrading the environmental performance of two houses on the Council’s Local Heritage List. This post shows what can be done to a more typical home in our borough.

No.1 Halliwick Road is an Edwardian semi-detached house typical of many in Barnet. Its owner, architect Ben Ridley, has radically upgraded it with the aim of making it an exemplar of sustainable retrofit on a constrained budget. When it was opened to the public earlier this month as part of London’s Open House Festival, it attracted scores of visitors.

Ben is the founding Director of Architecture for London https://architectureforlondon.com/, a practice with a track record of domestic and larger projects completed since 2009. Several have been published and won awards. He has expertise in Passivhaus design, an approach originating in Germany that through excellent thermal insulation, scrupulous airtightness and mechanical ventilation and heat recovery (MVHR) enables houses to provide comfortable living conditions with minimal use of energy.

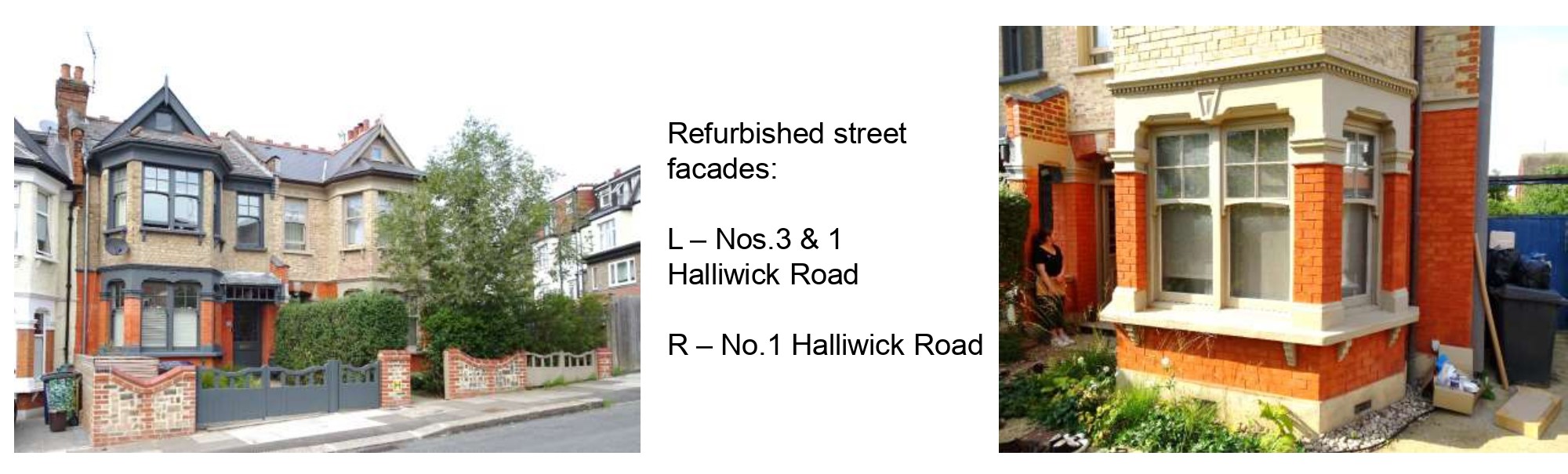

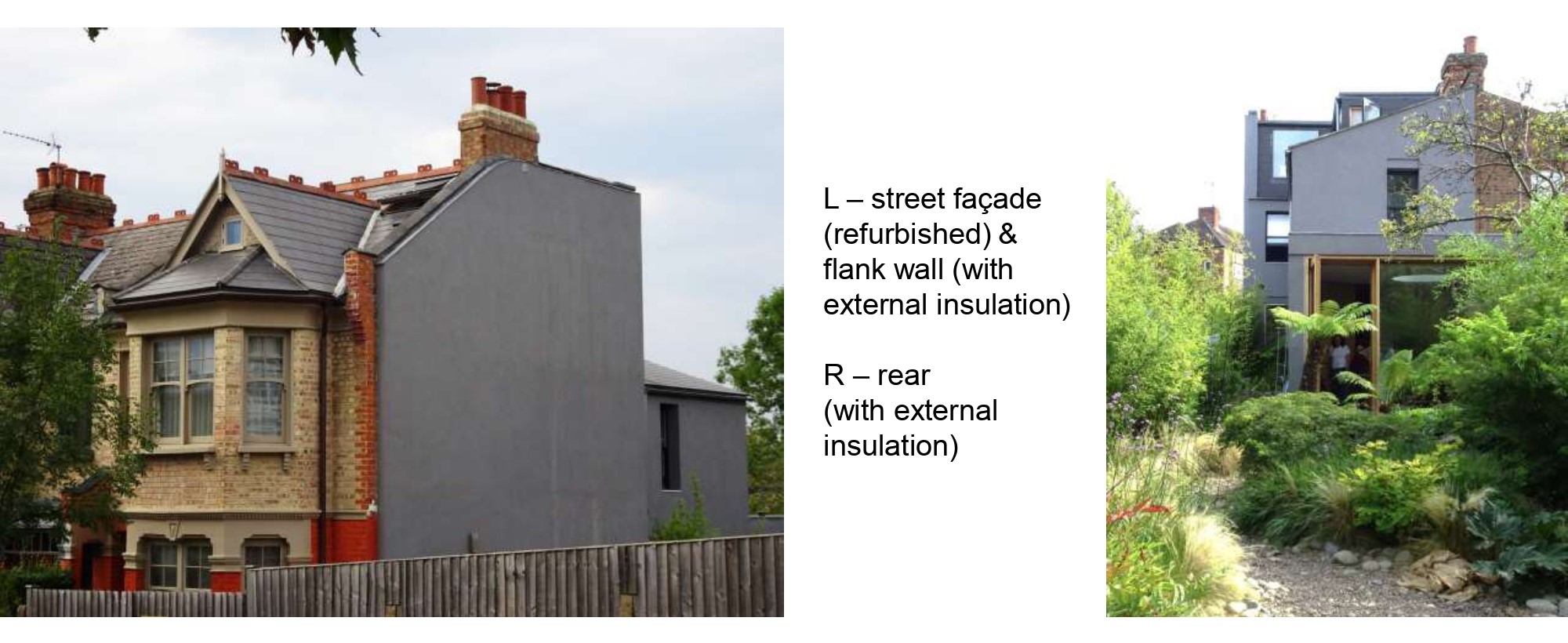

Ben refurbished the façades of the existing house and its neighbour so that, seen from the street, they retain their traditional character.

This was achieved by insulating the front brick wall internally with 65mm of wood fibre finished with 10mm of lime plaster. The flank wall and the upper floor to the rear were insulated with 170mm phenolic insulation and coated with a grey render.

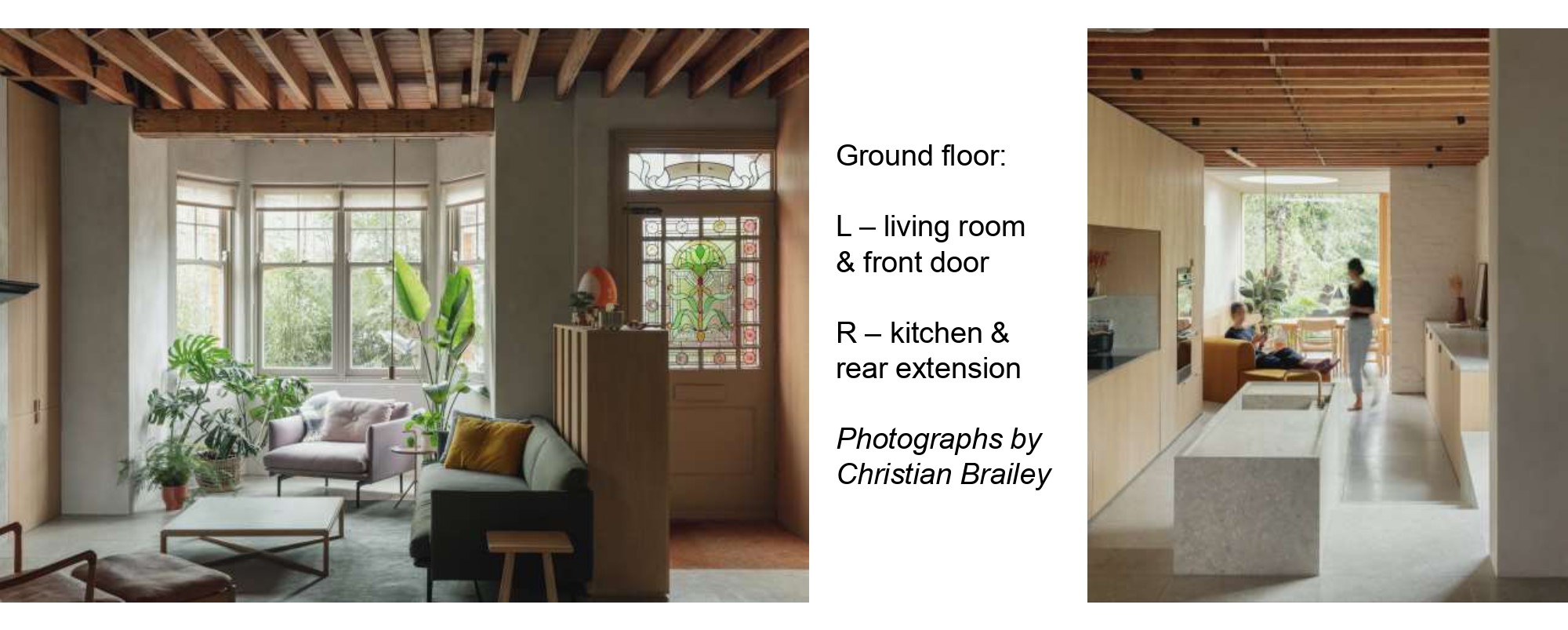

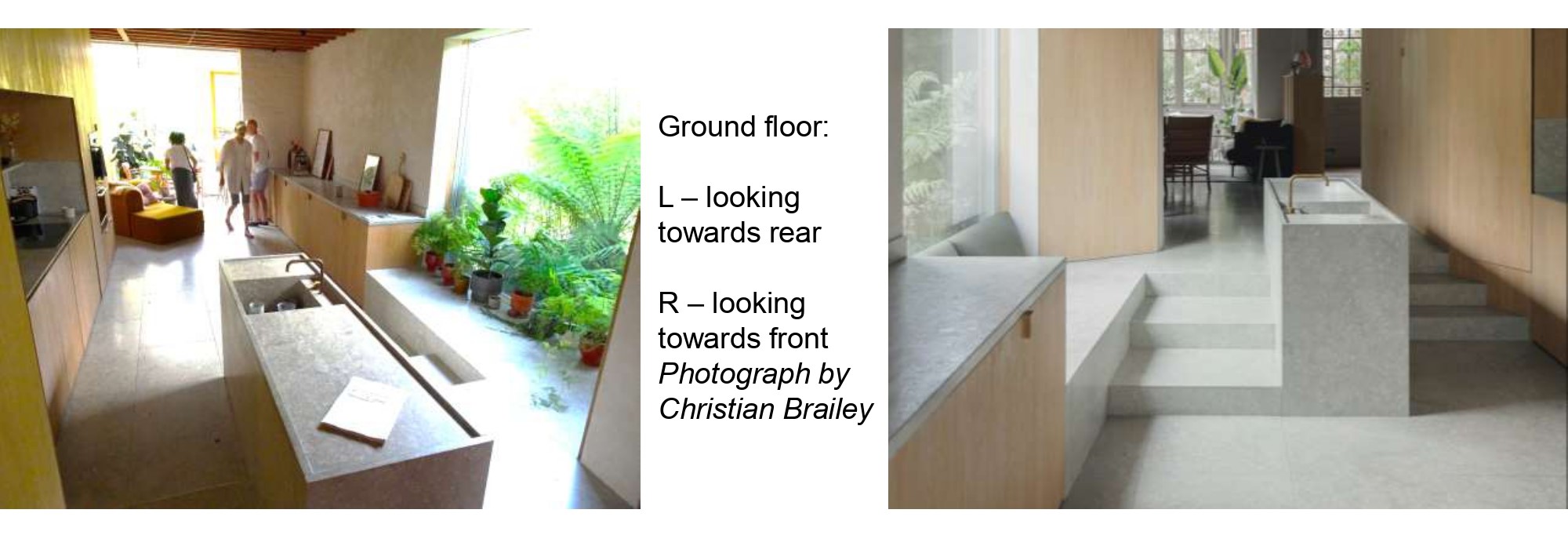

Internally, the ground floor has been almost completely opened up. This was not necessary environmentally, but provides a great sense of spaciousness and light, with daylight flooding in on three sides.

A back extension was added to the ground floor with walls of prefabricated 172mm structural insulated panels (SIPs).

Triple glazing was installed throughout. New double glazed vertical sliding sash windows were fitted, and behind them demountable secondary glazing panels are fixed and removed in summer. Continuous curtains provide additional thermal and acoustic insulation as well as privacy.

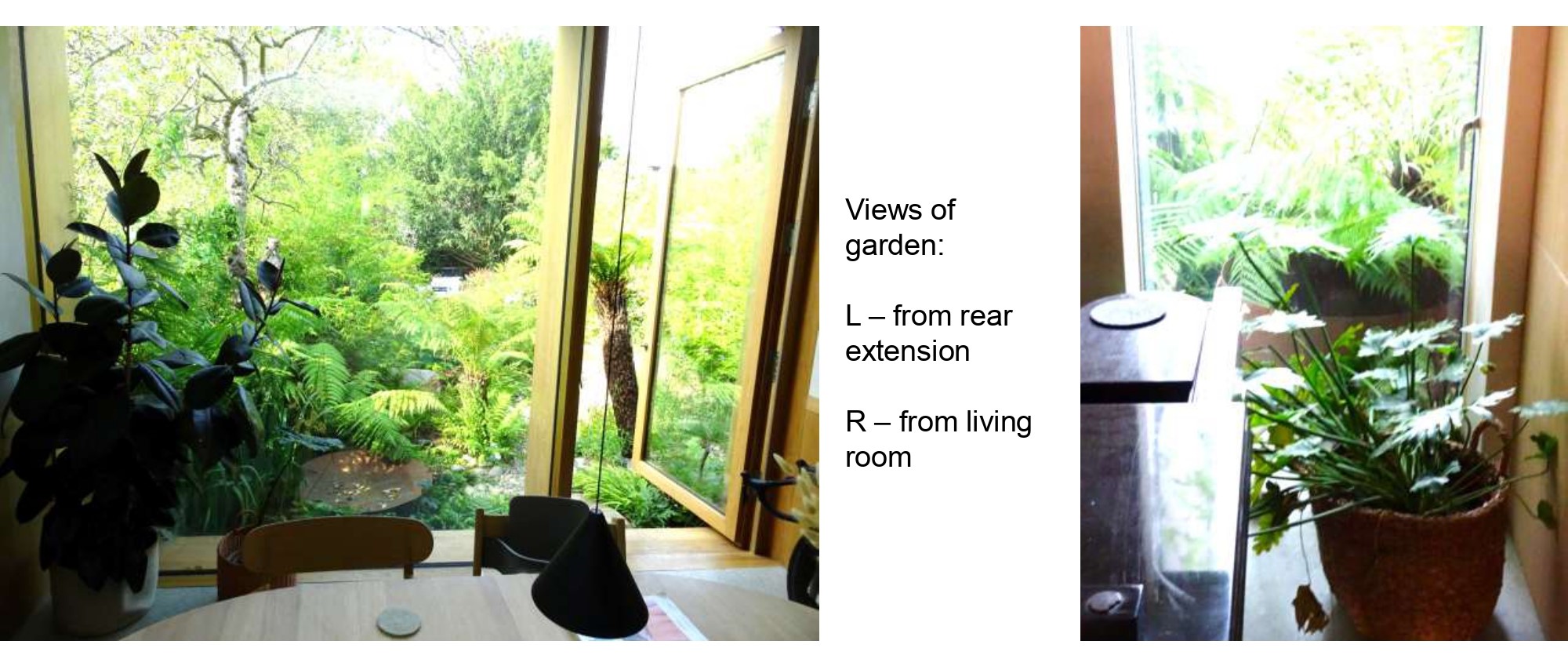

New windows are simply framed in wood and offer dramatic uninterrupted views of the greenery outside. A low-energy MVHR system ensures a supply of fresh, filtered and pre-warmed air when the windows are closed. Hidden ducts distribute fresh air and extract vitiated air via the roof.

The original suspended timber ground floor was overlaid with large Italian marble slabs for their visual quality and thermal mass. The void below was packed with insulation with sub-floor air vents to avoid condensation and decay. First floor timber joists and boards were exposed and cleaned up, and sound transmission between floors deadened by acoustic quilt. A wet underfloor heating system supplies the little space heating that such a well-insulated house needs.

The staircase has been replaced by a more compact one of plywood. A ground floor toilet is tucked underneath it. On the first floor is a new toilet and bathroom lined with limestone and wood. The existing loft has been converted into a bedroom and TV room.

The use of steel and concrete, which require large quantities of carbon to make, has been significantly reduced, with no steels used in the loft conversion.

The end result is a striking combination of traditional and contemporary craftsmanship that achieves a Passivhaus standard U-value of 0.15 or better (with the exception of the internally insulated front façade). The overall cost was around £250k + VAT – good value considering the extensive floor area (190sq.m.), especially at a time of high inflation and construction costs.

Ben Ridley has shown one way of upgrading an old house environmentally: there are others. But whatever you chose to do, it’s vital to (1) get appropriately qualified advice; (2) assess the whole building, its site and surroundings (even if your project has to be carried out in stages); (3) evaluate the likely costs of different options and possible sources of funds; and (4) use experienced contractors.

That’s easily said but in practice very challenging to achieve. The carbon reduction targets set by the Government are commendably ambitious, but to help meet them the only funding currently on offer to home-owners is grants of £5,000 for the installation of heat pumps. Although the need for better training of designers, engineers and builders has long been recognised, we also have a national skills shortage.

In Barnet, Council has launched some worthwhile initiatives following its declaration of climate emergency in May 2022, but the Barnet Sustainability Strategy Framework focuses, understandably, on improving the energy efficiency of Council-owned property to help achieve net-zero council operations by 2030.

As part of Building a sustainable future for Barnet, the Council also wants to ensure residents have access to the information they need to make sustainable choices. That would be a valuable start, but we’ve yet to find out how they propose to provide it.

Both Council and Government must do much more. As Marianne Nix, a Barnet Society member and house-owner keen to follow best practice says,

‘I can’t see how ordinary families will be able to manage. I can see the consequence – a lot of old buildings will be insulated incorrectly with all the wrong materials being used, and causing more issues and damage to properties in the long run.’

For these reasons the Barnet Society supports United for Warm Homes, a campaign by Barnet Friends of the Earth to petition MPs for:

- Urgent support for people dealing with sky-high energy bills.

- A new emergency programme to insulate our homes.

- An energy system powered by cheap, green renewables.

Please click this link to add your own support.

If you’re wondering what to do about your own home, the following sources of information may be helpful:

- The Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings (SPAB): https://www.spab.org.uk/advice

- Green register: https://www.greenregister.org.uk/the-register/

- Historic England: https://historicengland.org.uk/advice/climate-change/

- Low Energy Transformation Initiative (LETI): www.leti.uk/retrofit

- Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA): https://find-an-architect.architecture.com/

- Trustmark (Government-endorsed quality scheme): www.trustmark.org.uk/homeowner

I’m most grateful to Ben Ridley for technical information and Dave McCormick for environmental advice on this article.

Tags: #Barnet Council #Climate Change #Environment #Friends Of The Earth #Improvements #Net-zero #Sustainability

2 thoughts on “Greening Barnet’s existing homes”

Comments are closed.

So spend £300k and save perhaps £1k per year on energy. Profit in 300 years – soon we’ll all be millionaires!