Bringing to life fascinating history of eminent women who once lived in and around Barnet

A two-century old gravestone in Monken Hadley churchyard was the final stop on a guided walk around locations associated with inspirational women from Barnet’s past.

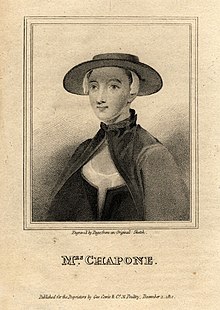

“Here lieth the body of Hester Chapone” – a celebrated campaigner for women’s equality whose encouragement for women’s self-improvement inspired Barnet historian Dr Susan Skedd to organise four well-attended tours around the town.

Dr Skedd had specialised herself in studying the history of girls’ education in the 18th century and during lockdown in March 2021, she was surprised to discover that such an eminent female author had lived locally.

Hester, who was a writer and supporter of the mid-18th century women’s social and educational movement known as the Bluestockings, spent her final years at Monken Hadley.

With the help of assistant churchwarden Katie Morris, she cleared the gravestone of moss, earth, and grass to reveal Hester’s name and inscription.

Dr Skedd said her research into Hester’s life, and her realisation that she was buried in Monken Hadley church of St Mary the Virgin, spurred her on to raise awareness about Hester’s life and to generate greater interest in the history of women in the locality.

“I was fascinated to learn that such an eminent female author had lived locally, and I was determined to highlight the lives of celebrated women from Barnet and Hadley whose achievements have been overlooked.”

Two tours, starting at Barnet parish church of St John the Baptist, were arranged for early March to mark International Women’s Day. Such was the interest that Dr Skedd had to organise two additional walks.

Another highlight of the tour was to stop nearby in front of Gladsmuir, one of the prominent houses facing Hadley Common, which in previous years was known as Lemmons, and was the home of one of Dr Skedd’s favourite authors, the late Elizabeth Jane Howard.

Howard was best known for writing the Cazalet novels and she lived at Lemmons with her third husband and fellow author Kingsley Amis, between 1968 and 1976.

During the visit to the churchyard – where Hester Chapone’s gravestone had to be given a gentle brush down to clear leaves and debris – Dr Skedd took full advantage of the setting as she outlined how it came about that Hester moved to Monken Hadley and died in 1801.

She had been a key member of the Bluestocking movement having had an impressive education in French and Latin and had started writing from the word go.

In 1754 Hester, daughter of Thomas Mulso, got engaged to a young law student, John Chapone, but her parents were against them getting married. In the event, six months after their wedding in 1760, her fiancée died.

Well before her engagement she had in fact been in correspondence with an eminent male novelist about the right of parents to intervene in the marriage of their daughters – and Hester had made it clear she believed women should be allowed to follow their heart.

In 1773 she wrote Letters on the Improvement of the Mind, which became her most popular work on the self-improvement of women, and which went through 30 reprints, and was still being published in the 1830s.

The letters were written initially to her 15-year-old niece, and they focussed on encouraging rational understanding through the reading of the Bible, history, and literature, as well as the study of book-keeping and household management.

Except for some earnings from her literary work, Hester had little other income and with the support of others in the Bluestocking movement she moved to Monken Hadley where she lived with the rector whose daughters were also inspired by Bluestocking thinking. Hester had been in poor health and died on Christmas Day.

Dr Skedd, a Barnet Society committee member, who regularly leads walks in London for English Heritage, believes Monken Hadley’s tally of eminent women needs greater recognition.

Not far from the church facing Hadley Green is Monkenholt, a Georgian residence, that was once the home of the late Dame Cicely Saunders, the Barnet-born founder of the hospice movement.

She established the world’s first purpose-built hospice in 1967 – St Christopher’s Hospice, at Sydenham in south-east London – and she was a pioneer in the importance of palliative care in modern medicine.

Dame Cicely, who died in 2005, spent her childhood at Monkenholt – a house that the Barnet Society President Aubrey Rose says is now a “must” for being awarded a blue plaque.

English Heritage says those honoured with blue plaques must have been dead for 20 years, but Mr Rose believes there is every justification for the rule being relaxed with regard to women given the discrepancy in the number of women who have been honoured in this way.

2 thoughts on “Bringing to life fascinating history of eminent women who once lived in and around Barnet”

Comments are closed.

Thanks for the footnote, Graham – it’s a shame that the stone-mason wasn’t on form the day he carved Mrs Chapone’s memorial.

I looked at the image of the gravestone, and read the name Chopoxe,

so some searching, and found a footnote in ‘the Gentleman’s Magazine volume XX, July to December MDCCCXLIII’ (1843) page 349. stating that two errors were made by the sculptor, and alterations were made by carving an A and N over the O and X.

weathering seems to have undone this correction.