Barnet’s biggest environmental challenge?

In Barnet, the biggest cause of climate change is housing. Homes emit around 50% of the carbon released in our borough. Radically reducing those emissions by upgrading the environmental performance of our homes is the most urgent and useful thing that many of us can do. It will also generate employment, substantially reduce our energy bills and – done properly – improve our health.

Over two-thirds of Barnet’s housing stock was built before 1944, and over 85% of it is likely still to exist in 2050. Today, the median Energy Performance Certificate (EPC) rating of existing homes in Chipping Barnet is only about 56%. Retrofitting them is therefore critical to achieving Net Zero.

The Barnet Society supports United for Warm Homes, a campaign by Barnet Friends of the Earth to petition MPs for:

- Urgent support for people dealing with sky-high energy bills.

- A new emergency programme to insulate our homes.

- An energy system powered by cheap, green renewables.

Please click this link to add your own support!

The technical and aesthetic challenges of bringing old houses up to modern standards mustn’t be under-estimated. It’s also financially challenging – but will only get more expensive the longer we delay. To illustrate the challenges – and to indicate some ways in which they can be met – this and my next web post will look at a couple of examples in Barnet.

The first is an attractive Arts & Crafts house that is on Barnet’s Local Heritage List, but in need of repair and improvement to reduce its energy consumption.

The second, which I’ll look at in my next post, is a more typical semi-detached house that has just been radically upgraded by a local architect, and which was opened to the public as part of London Open House earlier this month.

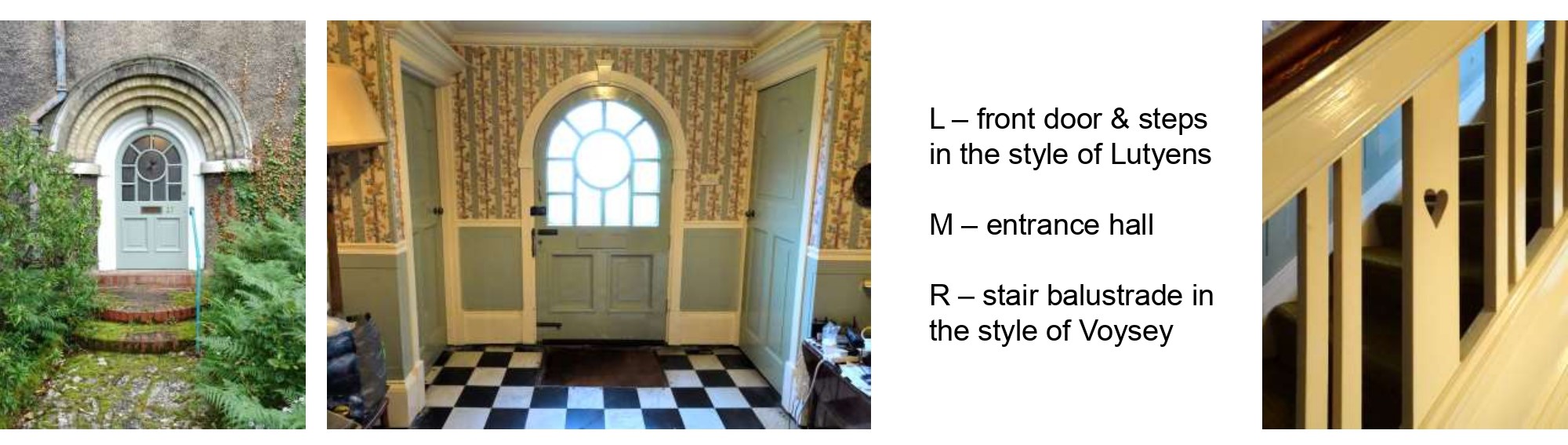

Nos. 26 & 27 Manor Road in Chipping Barnet is a pair of semi-detached houses dating from about 1906. The architect isn’t recorded, but the design shows the influence of Lutyens and Voysey. No.27 was the home of Peter and Doreen Willcocks, who were stalwarts of the Barnet Society and Barnet Local History Society. They moved in 60 years ago and the house is still occupied by family.

Nos. 26 & 27 Manor Road in Chipping Barnet is a pair of semi-detached houses dating from about 1906. The architect isn’t recorded, but the design shows the influence of Lutyens and Voysey. No.27 was the home of Peter and Doreen Willcocks, who were stalwarts of the Barnet Society and Barnet Local History Society. They moved in 60 years ago and the house is still occupied by family.

The future of both houses is uncertain. Being on the Local List they deserve careful conservation, but they’re increasingly expensive to maintain.

No.27 has been well looked-after – not surprisingly, since Peter was a national expert on the Building Regulations. But also unsurprisingly, it is showing signs of age. Fortunately its underlying structure seems generally sound and repairs should not be too difficult. What can and should be done to bring it somewhere near Net Zero standards without losing its beautifully crafted details?

Below are listed some improvements that could be made here, and to many other Barnet houses of similar vintage. However they are purely indicative and no substitute, it must be stressed, for a full survey and environmental diagnosis by a qualified professional.

Southerly-facing parts of the roof could be fitted with photovoltaic (PV) panels to generate solar energy. Although not applicable in the case of No.27, note that it may not be permissible to fit PVs on roofs in a Conservation Area.

Southerly-facing parts of the roof could be fitted with photovoltaic (PV) panels to generate solar energy. Although not applicable in the case of No.27, note that it may not be permissible to fit PVs on roofs in a Conservation Area.

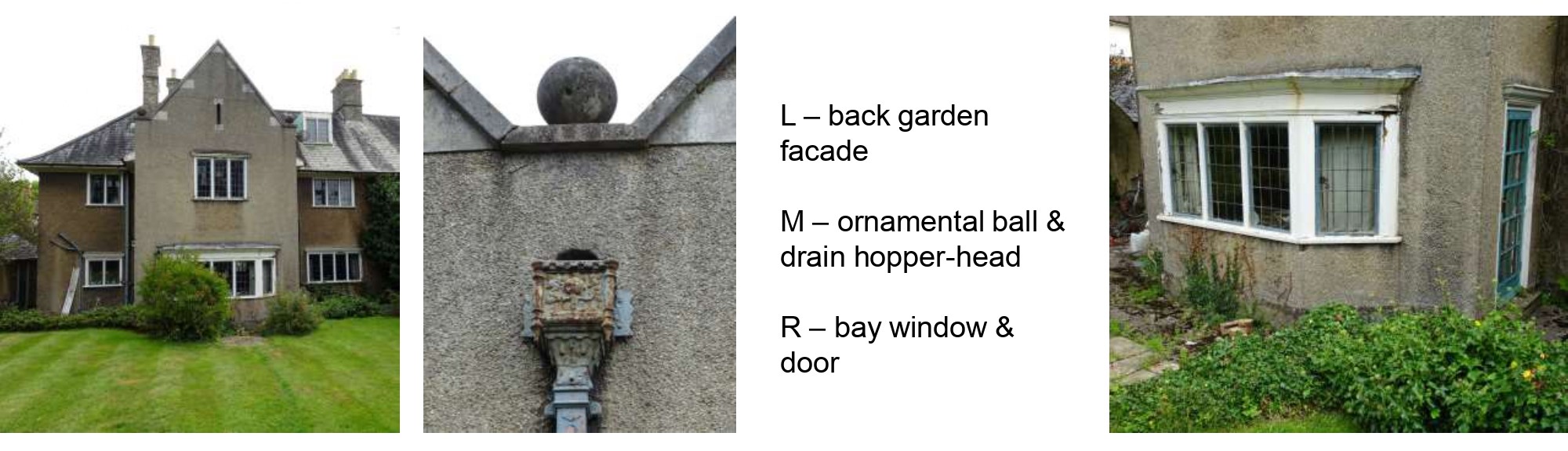

Guttering and drains are of cast iron with an ornate hopper-head. They should be kept if possible, or replaced with cast aluminium to similar profiles.

The rough-cast render is essential to No.27’s character. It may need repair or partial replacement, but that must be done with lime mortar to enable the brickwork behind to breathe. In unobtrusive places, it could be replaced with new external insulation finished with a thinner render to match the original in texture and colour. But this would need to be 50-100 mm thick which would have an impact on door and window reveals and cills, and require close-fitting eaves, gutters, downpipes and soil and waste pipework to be adjusted. Where internal insulation can be provided without unacceptable disturbance, all external walls can benefit from condensation-safe internal insulation, e.g. patent render with cork granules and lime skim-coat finish.

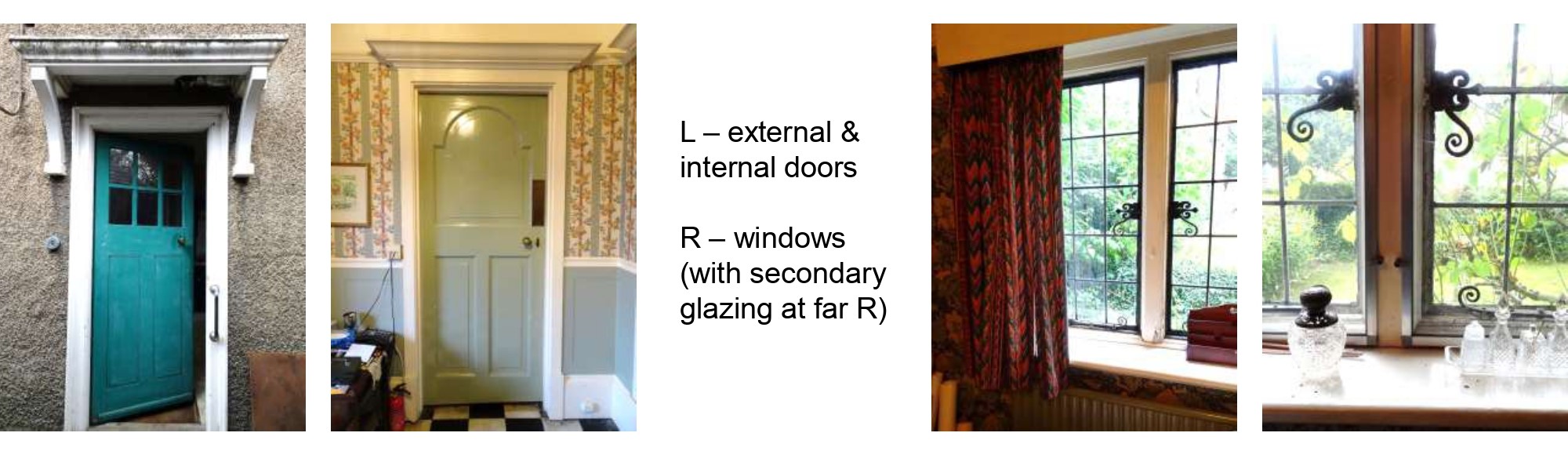

External and internal doors and frames are of solid wood with panels, often with their original ironmongery and Classical canopies or cornices above. The external doors would need draught-proofing.

The original lead-paned windows with their ornamental fasteners remain intact. Secondary glazing was installed remarkably discreetly by Peter Willcocks nearly 50 years ago: compare the original living room windows (above middle R) with the secondary-glazed ones in the kitchen (above far R). Today a triple-glazed unit would be considered.‘Slimlite’ and similar thin double-glazing units are available, some fitting into the traditional shallow glazing rebates. They are more expensive than normal double-glazed units but more elegant than secondary glazing.

Much of the ground floor is of timber boards, still in good condition. Underfloor insulation could be inserted between the floor joists, though care is required to retain, clear, and possibly increase the number of sub-floor vent bricks/gratings to ensure a through-flow of fresh air.

Several fireplaces survive, one with a magnificent Classical mantelpiece and surround. Most have been blocked up but include ventilation for their flues. The existing tall chimneys are features of the roof and in fair condition. They should be retained and could form part of a new mechanically controlled ventilation system with heat recovery.

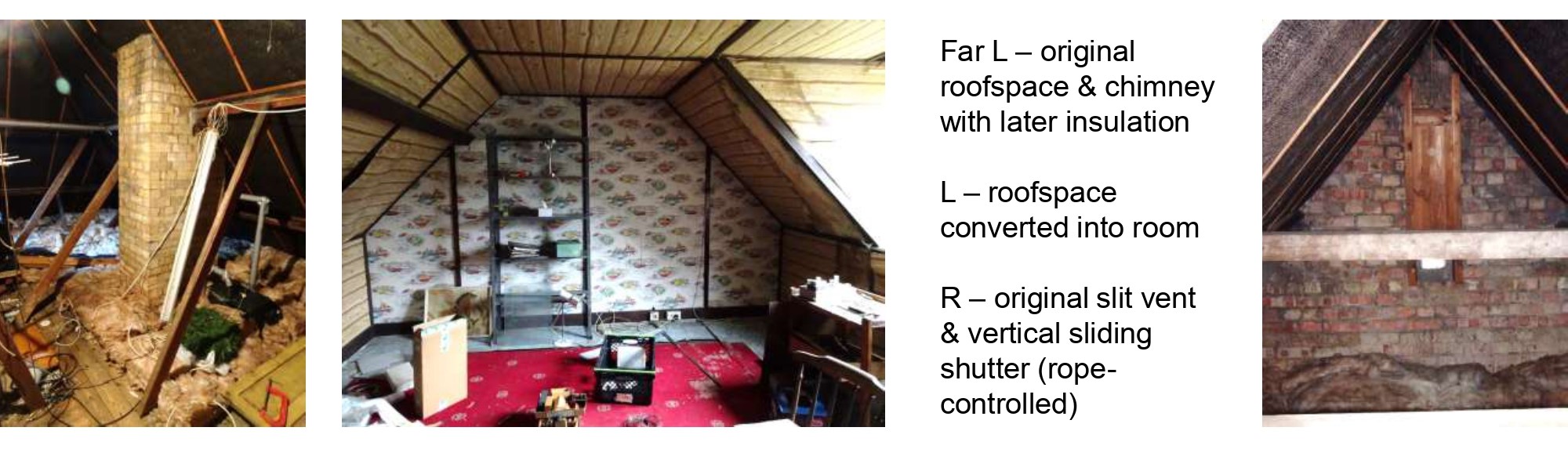

The roof spaces have been partly converted for storage and other use, but the existing structure – and even the vertical sliding shutters to the gable ventilator slits – remain in fair condition. The insulation should be greatly increased, however, and air leakage and condensation eliminated.

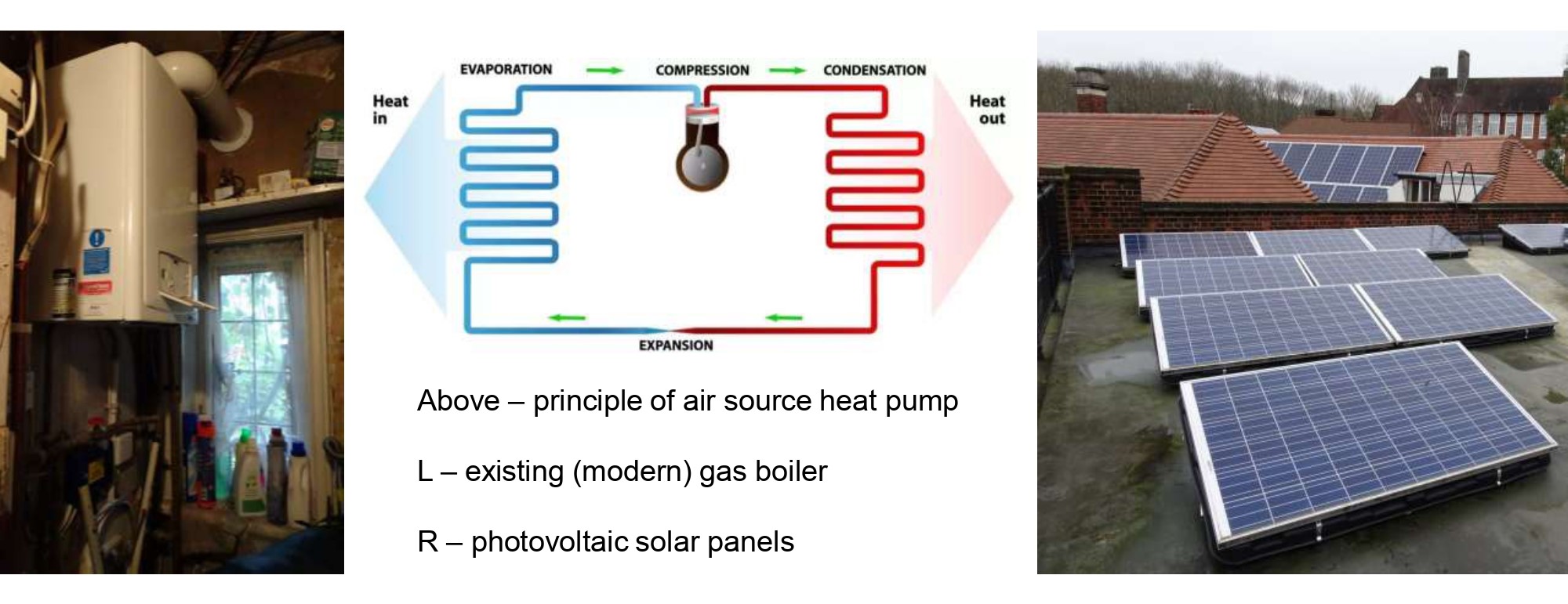

The existing gas central heating boiler and radiators have served well for decades, but the boiler will have to replaced before long by some new source – or combination of sources – of renewable energy. One could be solar panels (mentioned above). Air-source heat pumps (ASHPs) are increasingly being used, though their effectiveness depends on high levels of thermal insulation and airtightness, and often on larger and/or more efficient radiators. Whilst gas and oil-fuelled boilers continue in use, solar water-heating from a roof-mounted solar panel is a good way of mitigating fuel costs. This entails replacement of the standard hot-water storage cylinder with a well-insulated calorifier containing an additional heating coil connected to the solar panel.

The All-Party Parliamentary Group for Healthy Homes and Buildings points out that the introduction of energy efficiency measures must go hand-in-hand with the introduction of appropriate mechanical ventilation that can exchange toxic indoor air with fresh air, and with design measures that improve the overall comfort and wellbeing of all occupants.

To ensure both air quality and economical running, a building energy management system (BEMS) will be needed. But it must be properly installed, calibrated, commissioned and maintained.

Materials and workmanship must also be of appropriate quality. As well as looking right, the results must not impair the environmental performance of the building, for example by creating condensation and mould.

The suggestions above only scratch the surface. It’s vital to understand the construction of a house before specifying solutions, but getting good advice isn’t easy.

As Barnet Society member and sustainability expert Dave McCormick notes, ‘High energy prices might be persuading more people to consider green home improvements, but knowing where to begin is an issue for many.’ Or as Marianne Nix, another Society member and house-owner keen to follow best practice, puts it, ‘Finding suitable builders is like looking for a needle in a haystack. And I’m not sure I know what the needle looks like!’

Looking for that needle – and for expert advisers, designers, builders and funding – will be addressed in my next post.

I’m most grateful to Alan Johnson, Richard Kay and Dave McCormick for their advice on this article.

Tags: #Chipping Barnet #Climate Change #Environment #Friends Of The Earth #Improvements #Local List #Net-zero #Sustainability

2 thoughts on “Barnet’s biggest environmental challenge?”

Comments are closed.

Cannot allow caravan dwellers on a green conservation area which i love to walk in . It will ruin the unspoilt natural countryside

We cannot allow caravans with travellers or caravan dwellers to blight the countryside in a green conservation area which i enjoy walking in .