Transport is back in the news, with the government’s promises of a ‘bus revolution’ and renationalisation of rail services. As London expands into the Green Belt, it’s timely to review the state of transport in Barnet and neighbouring areas.

Background

Being an ancient market town at the top of a hill, Chipping (High) Barnet has long been dependent for its economy on traders, travellers, businesses and visitors, and this means roads and transport connections. The Great North Road and the Holyhead (St Albans) Road, supported by orbital connections to Watford and Enfield and many local minor public trackways, provided the means.

Transport used on Barnet’s roads remained mostly horse-drawn, with some exceptions, until gradually giving way to motorised vehicles after the 1st World War. Importantly, these exceptions included the electric street tramway which opened between Archway and Whetstone in 1905 and was extended to Barnet Church in 1907. That stimulated more house building on the level in High Barnet than had the steam railway to High Barnet in 1872. The other exception to note was the 84 motor bus route between Golders Green and St Albans via Barnet and South Mimms in 1912, which was the first successful regular motor bus service to run through Barnet High Street.

In the 1920s new bus links were established between Watford and Enfield via Barnet, and towards Central London via Muswell Hill and Camden Town, and to Potters Bar and Hatfield. With the introduction of pneumatic tyres, long distance coaches to the Midlands and North began to appear with pick-up/set-down facilities at Finchley and High Barnet and a regular service to Bedford with stops in Outer London including Barnet was established by Birch Bros. ‘Commuter’ limited stop services were also started between the home counties and Greater London via Barnet in1929/30, and these were absorbed into the Green Line network in the early 1930s.

Personal car use by local residents remained very low during this period, but photographs of Barnet High Street in the late 1930s showed some parking of private cars, and the provision of pedestrian crossing places signed with Belisha beacons showed there was a safety need to protect pedestrians from traffic flow in Barnet. Striped zebra crossings replaced Belishas about 1950, but it was not until the early 1960s that it was felt necessary to control where parking in Barnet should and should not take place on the roads and make off-street provision for cars in the town centre a necessity.

The opening of the M1 motorway, in stages at the southern end, the upgrading of the South Mimms – London Colney section of St Albans Road and the A414 access to the motorway hugely increased car usage between Greater London suburbs including Barnet and the home counties in the 1960s for both work and leisure travel. At the same time the upgrades to the strategic roads caused the diversion of the long-distance coach services which no longer served the High Barnet area. Green Line services lasted a bit longer, but a combination of suburban rail electrification and greatly increased traffic congestion reduced user levels to a point where the road services could not be economically viable.

Personal transport

Anyone who studies a scale map of the Greater London area will see that distances between the residential areas and town centre attractions are far greater in the outer reaches of the built-up area than in Inner London. A walk from house to convenient shops, banks, entertainment, schools and rail and bus connections which may be easy for those who live in, say, Kentish Town, become much more difficult and extreme north of the Finchleys and Muswell Hill. It is understandable that personal car usage is more widespread in these outer areas, and made the more acute where steep hills are part of the journey.

In the build-up to the climate change 2050 deadline it becomes vital that all public authorities recognise the need to work in co-operation to provide or secure a co-ordinated solution to this multi-disciplinary project. That would involve Highways England, TfL, the London Borough of Barnet, Hertfordshire County and Hertsmere District Council with public highway responsibilities and, where appropriate, planning, housing and environmental duties.

Co-ordination is required in the provision and user costs of on and off-street parking places, electric charging points where residents don’t have personal driveways, traffic speed limits, traffic schemes designed to eliminate moving vehicle emissions, pavement parking, pedestrian movement safety in residential areas as well as town centres, recognition of the heavy weight of electric cars and vans on local roads not constructed for regular use by them, and reliable provision of adequate road-based public transport on the existing network and in the design of new-build residential developments, to accommodate conventional bus services.

In Barnet it is noticeable that in recent years there has been a big increase in the number of transit-size vans travelling and parked on local main and side roads, both small trader and unidentified ownership. That in addition to online delivery vans.

Electric battery cars and small vans are likely to be the most popular zero-emission personal and trader vehicles in the near future, but that is not to say that other motive methods may be tried. Critical to the speed of conversion will be the availability of public charging points at affordable rates.

Increase in the use of electric cars and vans will lead to a decrease in the existing fuel duty and VAT paid by motorists. The government will want to recoup that income from motorists and this could mean some form of Road User Charging, the details of which are undecided and far from clear at present. It is an issue that is bound to some up for political and public debate in the coming years, so watch Barnet Society space!

Driverless cars/vans may be up and coming with their safe passage assured, even on roads used by conventional vehicles. The danger in the longer term is that the person in the ‘driver’s seat’ begins to lose their ‘streetwise’ knowledge which normally develops with driving experience. This could result in silly low-speed manoeuvres, or in more serious incidents on a fast road with junctions, both involving vehicle damage and often collisions causing personal injury. Both would currently be considered completely avoidable.

While pedal cycling and motor biking can reduce car use, the hilly nature of much of the High Barnet area rather deters local use for work and shopping purposes. However, for takeaway food deliveries biking avoids the use of small vans. The sporty pedal cyclists will help the coffee shop trade, but their ability to purchase more widely in Barnet is understandably very limited on such occasions! The speed of the Sunday pedal power is important for pedestrians to realise when crossing the roads. Use of the footway, particularly narrow pavements, by battery-powered scooters or cycles can also be a hazard for walkers, including the less agile and those using their mobile.

All this is a big ask, but needs to be addressed. Whether we like it or not climate change is going to produce extremes of weather, which is bound to affect roads and transport infrastructure and movement of people on the public highway, be they in vehicles, on feet or in wheelchairs. This is very relevant in hilly areas like High and New Barnet with catchment residences in adjacent valleys. Individual authorities may well prioritise the interests of their own residents, but the moving public are rightly concerned with journey time, safety, convenience and costs of travel and parking, not with which highway authority they are using on their travels. Those in transit are all equal ‘customers’.

Public transport

It is important to examine the role of existing scheduled public transport in the context of climate change and separately in those areas that are proposed for new-build housing within the Society’s sphere of interest in north Barnet and Enfield and adjacent parts of Hertfordshire. Predominantly this will concern local bus services and the few contract hire coaches that operate at school times. While the tube and rail services are a vital part of public transport, realistically it is unlikely that there will be any extensions or new stations in the foreseeable future in the Society’s interest area. Crossrail 2 proposals for a New Southgate branch to its service from south-west London and the reopening for passenger traffic of the Dudden Hill branch from the Brent Cross station to Acton and Hounslow have been very quiet in recent times. Both have possible extensions that would bring relevance to Barnet residents. But to concentrate on road-based public transport and access for users.

The way local bus services are organised within and outside Greater London are very different, and enshrined in different primary legislation. Outside London, private sector bus companies can operate local bus services on a commercial basis which they have ‘registered’ with the relevant area traffic commissioner. The operator decides on the route, the frequency, the hours and days of operation, the stopping and terminating stand places, the vehicle size and capacity and the fares to be charged. The local authority will check the physical implications of the registration, and has powers to provide subsidy to fill ‘gaps’ in the service provision it feels are necessary and affordable (e.g. Sunday, evenings, school time extra journey) via a tender invitation to interested private sector operators.

Within Greater London the planning of the whole local bus network, including the frequency, vehicle sizes and detailed design, fares and ticketing, stopping and standing places, bus priority measures, etc. and, prior to 1984/5, the actual operation of services, was the duty of just one central organisation with monopoly powers and responsibilities, ever since 1933. The London Regional Transport Act 1984 took ‘London Transport’ into central government control in view of the impending abolition of the Greater London Council and required it (LRT) to involve private sector bus companies in the operation of London local bus services. This was 100% achieved by 1995 and made practical through an efficient tendering process.

When the Greater London Authority and TfL were established in 2000, the tendering system continued. TfL has powers to extend its services into the Home Counties to reach important traffic objectives within easy reach. This it does all around London, with Oyster validity throughout. Private sector companies can operate local bus services within Greater London which are not part of the TfL network, but they need to obtain a ‘London local service licence’ from the metropolitan traffic commissioner to do so. Such services are not part of the TfL Oyster fares and ticketing system.

Cross-boundary bus services

Nearby Hertfordshire places are served by regular daily TfL local bus services as follows: Watford from Wealdstone and Harrow; Watford from Stanmore and Edgware; Borehamwood from Edgware; Borehamwood from Arkley and High Barnet; Potters Bar from Cockfosters and Southgate; Potters Bar from Chase Farm and Enfield.

London buses absorbed the Potters Bar – Enfield link from the National Bus Company in 1982 when Hertfordshire withdrew funding from the St Albans – Potters Bar section of the 313 service. This led to the diversion of bus 84 from South Mimms via Potters Bar en route to High Barnet in June 1986. In October 1986 the London Bus operator registered the 84 as commercial between St Albans and New Barnet. By 2015 Metroline were providing a 15-minute service in Mon-Sat shopping hours (30 minutes on Sundays) with hourly services to late, but in a period before it withdrew the service south of Potters Bar, the daytime service was halved. The regular provision of a local bus service between Barnet and Potters Bar ceased in 2022 for the first time in 101 years, and it is sad and surprising that TfL declined to participate in ‘filling the gap’, especially when it maintains daily tendered links between Potters Bar and Southgate and to Enfield, amongst many other cross-boundary services all around Greater London. Hertsmere District Council has now provided funding for a limited Mon – Sat daytime service between Potters Bar and Barnet. This is very welcome, and we have to wait to see if patronage increases and can justify a frequency increase.

Another cross-boundary local bus is UNO’s commercial all-day service 614 which serves Barnet Spires and Arkley en route between Hatfield and Queensbury. It connects with Hatfield via St Albans Road and the A1(M) where it serves the University of Hertfordshire, the Galleria and the rail station for Hatfield House. In the other direction it runs via Stirling and Apex Corners, Edgware (including the Community Hospital) and Burnt Oak. It provides a half-hour service on Mon – Fri, hourly in evenings and all day Sats. TfL Oyster and Travelcards are not accepted, but Freedom Passes are. Single journey cash fares are capped at the present time at £2 through a central government grant which expires in 2025. We shall have to see what the new government will do.

To complete the cross-boundary picture, TfL does run a school-time only local bus (626) between Finchley, New and High Barnets and the Dame Alice Owen School in Potters Bar, but although it is available for all users, it only serves Potters Bar (proper) in the morning run, as afternoon journeys only emerge onto the Great North Road at Ganwick Corner.

Public transport in new-build developments

New-build residential developments need to be for about 5,000 people to justify a new bus service, although if there is an existing service nearby which can be diverted easily then smaller developments can be served. All residential units need to be within 400 metres (5-minute walk) of a bus stopping place, and roads serving buses (both ways) need to be a minimum of 6.75 metres wide assuming no on-street parking by cars/vans (DoE circular 82/73).

Routeing through the estate needs to be progressive if the bus does not terminate there – double runs should be avoided and given bus stopping places are 400 metres apart on average, residential cul de sacs should be no longer than 200 metres from the bus route. New developments in urban areas should not be reliant on Dial-a-Ride minibuses – minibus drivers do not get mini wages and there is the added cost of dealing with the travel requests.

General comments

There has been a lack of care by TfL staff in the last 10 years to deal with issues that arise with some bus services in the outer reaches of Greater London in the hilly areas in and around High Barnet and its residential catchment communities. Water, gas leaks and road works in various parts of the Chipping Barnet constituency have resulted in dramatic diversions and withdrawal of some services, often distant from vulnerable residential areas at the bottom of steep hills which have been isolated for weeks on end.

More disturbing are the sudden and frequent withdrawals of 184 buses for several afternoon/evening hours when users, including the less agile, are returning from Barnet with shopping to their homes in the Manor Road/Mays Lane valley. Reliability of some bus services has suffered, not helped by an absence of bus stop timetables for up to four years in Barnet High Street and The Spires. Low floor and electric buses should be welcome, but bus stops are London Buses’ shop window where those who do not have a computer or smart phone depend on information about the bus service they require.

There is a clear need for a Ms or Mr Bus with knowledge of the local area and its hills and valleys to recognise and resolve the issues that can arise so that users – including those who are less agile or have buggies in tow – can be confident that the planned service can actually be run reasonably reliably. When the only bus service on a section of route is withdrawn for a long time, usage does not come back easily when it returns, and that can result in a drop in planned frequency.

On a different but connected tack, the Mayor of London proposes the Superloop 2 for limited stop services between Harrow, Barnet and Enfield. We will wait for details of this exciting and potentially useful project to be consulted on, but some issues need to be pointed out and addressed.

Existing Superloop 1 services around London rightly received a lot of local publicity. Less attention was paid to the associated reductions in existing parallel stopping service frequencies. With the Superloop 2 proposal between Barnet and Enfield the 307 service is vulnerable to altered frequencies which, given the hilly nature of the routeing, needs detailed attention. The Superloop service will only use the main and busy stops en route. Sections like Cat Hill and Slades Hill may not have a Superloop stop. Nearby schools and hospitals may have to depend on a reduced service for their pupils, staff and outpatient appointments. This is just to draw attention to the issue, not to criticise the project. The Bus Planning Team at TfL headquarters plan expertly, but there are lots of intricate details affecting this project which understandably they may not be aware of. It underlines the need for locally-based TfL staff in Outer London who are familiar with the needs and concerns of the local communities.

Peter Bradburn BA, CMILT

Peter Bradburn BA, CMILT

I have lived in the Chipping Barnet constituency virtually all my life and enjoyed a 45-year career in transport planning, mainly in the London region but also in northern and west country cities. Experience was plentiful in this multi-disciplinary business and was enhanced by those I met, at all levels.

I joined the Barnet Society committee some 35 years ago, and have advised it on local transport issues from time to time ever since. I believe that the influence of transport on the key housing, Green Belt and town centre aims of the Society at the present time is more important than ever to co-ordinate with other authorities in this outer edge of Greater London.

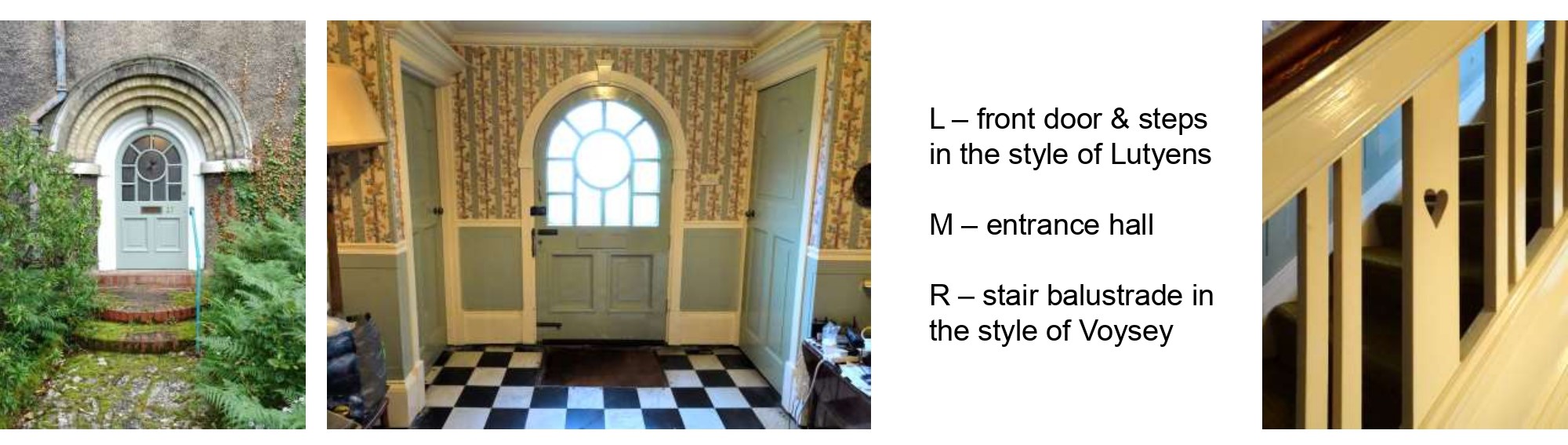

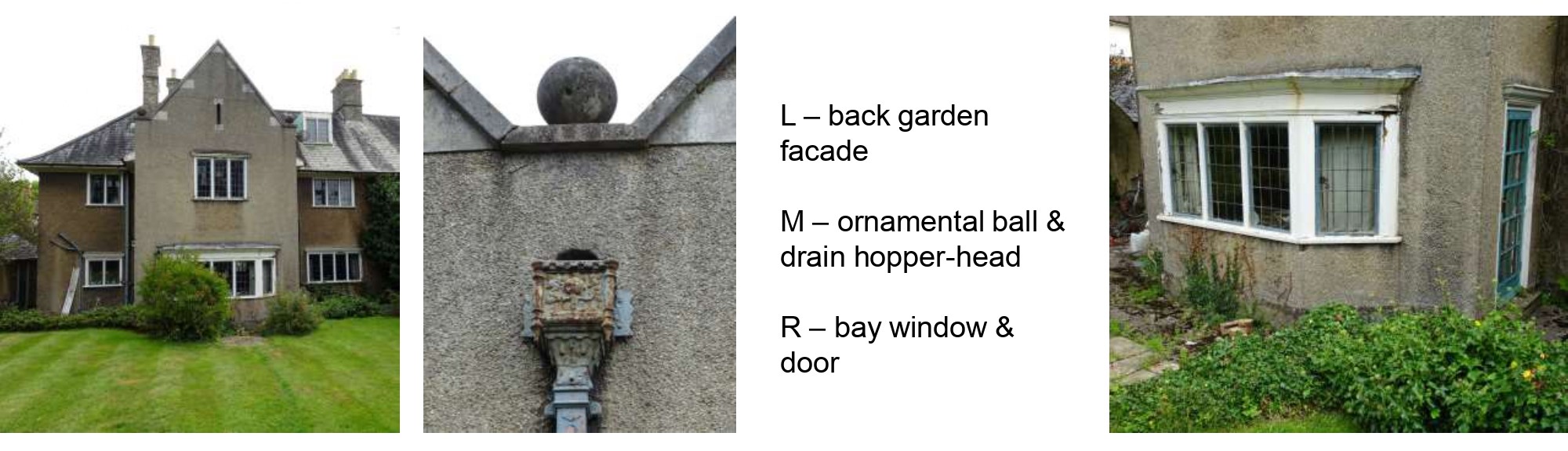

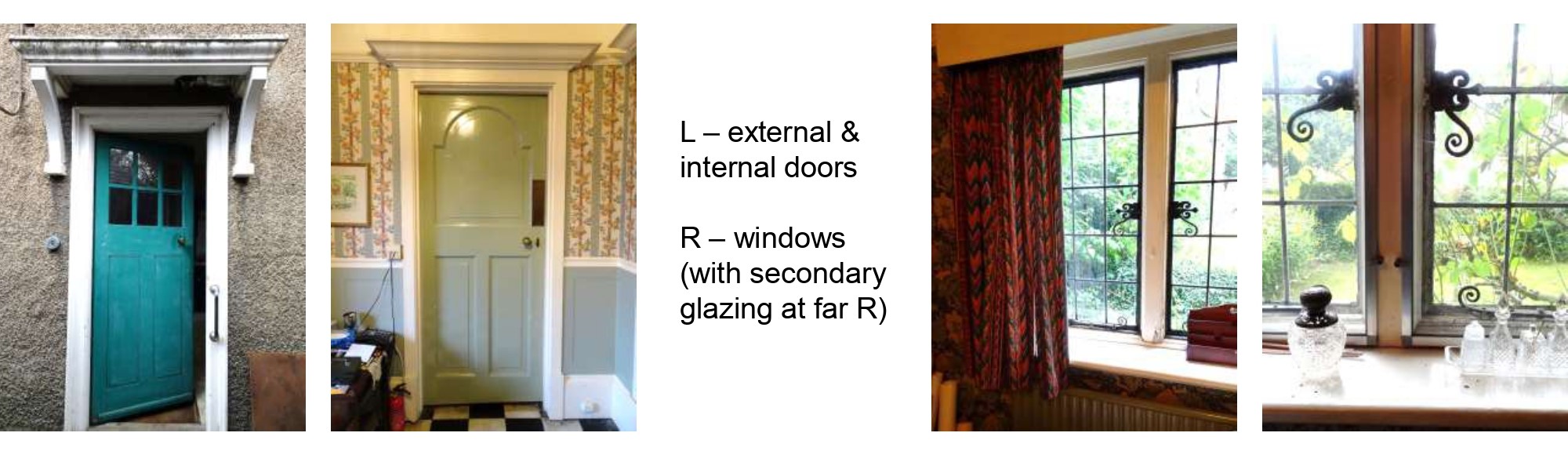

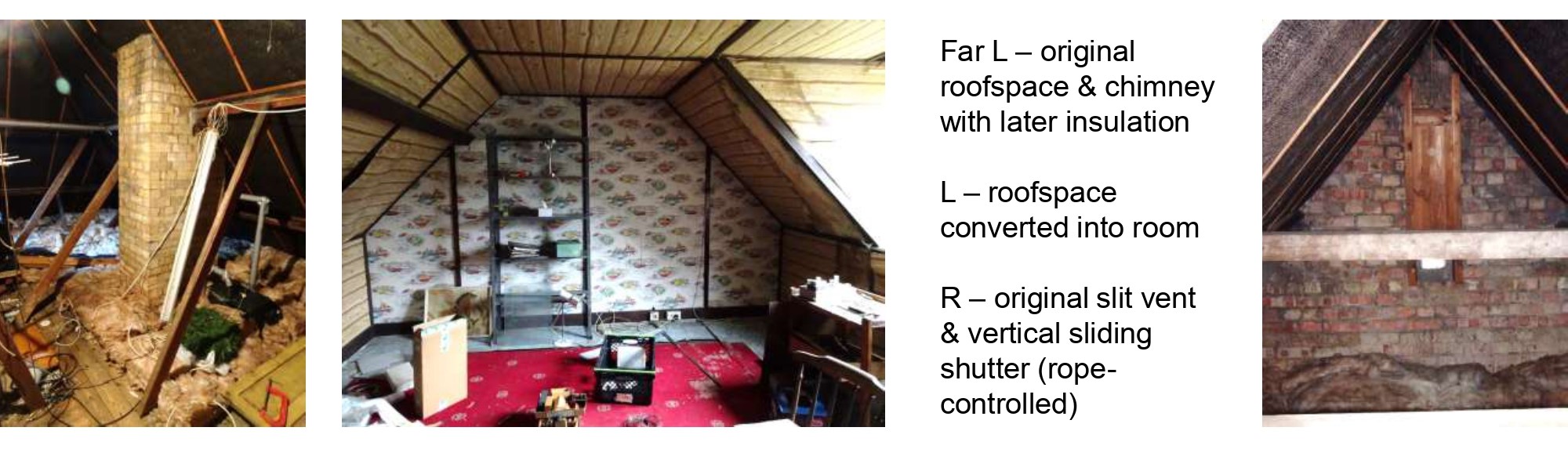

Nos. 26 & 27 Manor Road in Chipping Barnet is a pair of semi-detached houses dating from about 1906. The architect isn’t recorded, but the design shows the influence of Lutyens and Voysey. No.27 was the home of Peter and Doreen Willcocks, who were stalwarts of the Barnet Society and Barnet Local History Society. They moved in 60 years ago and the house is still occupied by family.

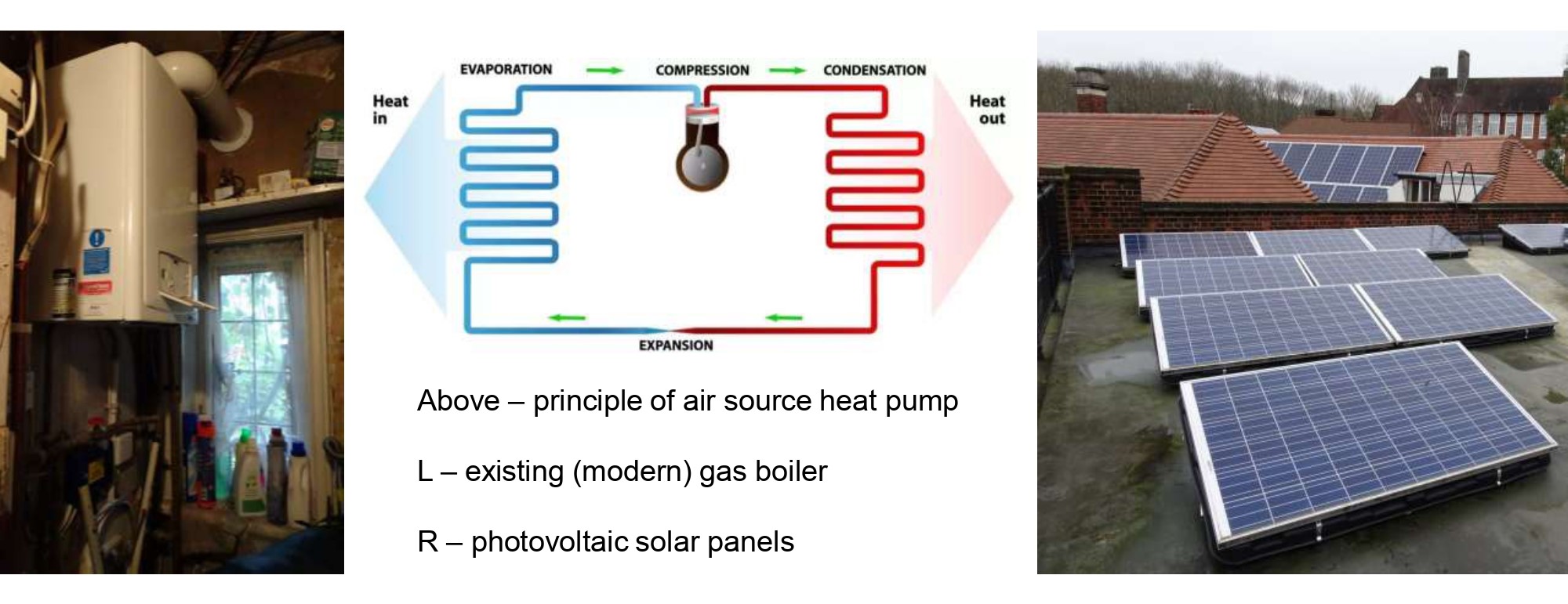

Nos. 26 & 27 Manor Road in Chipping Barnet is a pair of semi-detached houses dating from about 1906. The architect isn’t recorded, but the design shows the influence of Lutyens and Voysey. No.27 was the home of Peter and Doreen Willcocks, who were stalwarts of the Barnet Society and Barnet Local History Society. They moved in 60 years ago and the house is still occupied by family. Southerly-facing parts of the roof could be fitted with photovoltaic (PV) panels to generate solar energy. Although not applicable in the case of No.27, note that it may not be permissible to fit PVs on roofs in a Conservation Area.

Southerly-facing parts of the roof could be fitted with photovoltaic (PV) panels to generate solar energy. Although not applicable in the case of No.27, note that it may not be permissible to fit PVs on roofs in a Conservation Area.

Robin Bishop posted a comment on Public consultation on proposed new house in Christchurch Lane spinney

Tom posted a comment on Public consultation on proposed new house in Christchurch Lane spinney

TERENCE DRISCOLL posted a comment on Years of neglect prompting residents’ bid to get Barnet’s former Quinta Youth Club registered as asset of community value

Disgruntled Resident posted a comment on Sad loss of an imposing Victorian villa built when New Barnet was developed after the opening of its main line railway station