Looking back on 450 years education at QE Boys’ — former headmaster relives era of dramatic change

For 30 years Queen Elizabeth’s School, Barnet — which is celebrating its 450th anniversary — was at the apex of a clash between opposing education policies which were being pursued by Labour and Conservative governments, and which at the time split the country.

These divergent teaching regimes were destined to fail, but the school now has an assured future says former headmaster Dr John Marincowitz in a new history of what is still known locally as QE Boys.

In 1994, QE ended a 23-year experience as comprehensive school, reverted to its previous status as a grammar, and has now become heavily oversubscribed.

It administers its own selection process which over two days last September attracted 3,500 applicants at an annual entrance exam for 180 places.

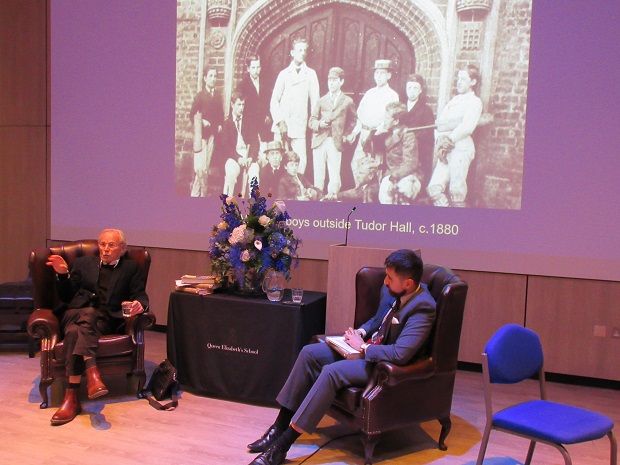

At the official launch of his book (1.3.2023) Dr Marincowitz suggested that when Barnet parents backed the comprehensive system proposed by the Labour government, they were “lured by false promises”. (see above, Dr Marincowitz (left) and Surya Bowyer, former head of library services and curator of QE collections)

A survey by Barnet Council in 1970 showed that 80 per cent of parents were demanding an end to the 11-plus exam, abolition of both grammars and secondary moderns, and their replacement with comprehensive schools.

Dr Marincowitz accepted that education in the pre-comprehensive era had been a disaster: the 75 per cent of children who failed the 11-plus were condemned to attend secondary moderns which were “just a containment exercise” and which were a “disaster of missed opportunities”.

If secondary moderns had provided viable career progression routes for less academically able pupils with more practical and technical education, they might have thrived alongside grammars.

QE went comprehensive in 1971, becoming an all-ability school under the control of Barnet Council, open to boys within its High Barnet catchment area.

But within less than a decade the “writing was on the wall” for comprehensives. Barnet’s exam results had started to go down.

“Results at QE Boys’ were abysmal; the number going to university shrank; and by the late 1970s people in Barnet had lost confidence in the comprehensive system.”

When the Conservatives were elected in 1979, the government began monitoring schools by results and educational standards were uppermost.

QE was one of the first schools to take advantage of grant-maintained status, taking back control of its finances from Barnet Council in 1989, and then securing the right in 1994 to reinstate a selective admissions policy and regain grammar status.

In describing the conflicts that occurred, Dr Marincowitz said he had come to admire the two headmasters in control of the school during this troubled era – Ernest Jenkins (1930-1961) and Tim Edwards (1961-1983).

They had sharply contrasted views of education, “and could hardly have been more different”, but each administered unsustainable education regimes and their legacies did not endure.

“Jenkins was undone by the disaster of the tripartite system…The demise of the comprehensive system was the result of changing attitudes and a loss of confidence.

“They were both men of their time, their legacies undone by changes around them.”

Looking to the future, Dr Marincowitz predicted that there was unlikely to much change in the current pattern of secondary education. He did not think there was any chance of seeing the wholesale return of grammars across the country or a proliferation of comprehensives.

Governments had found a consensus: schools had their autonomy, they thrived on having autonomy over teaching and financial affairs.

Selection had spread throughout the secondary system to varying degrees – 100 per cent in grammars, 50 per cent in some schools and 10 per cent in others. Some schools had banding on admission, others by setting.

Selection, whether or not in surreptitious forms, had raised standards.

“Schools in London used to be the worst in the country and now they are the best in the country because of standards. We won’t go back to standardised comprehensives or local authority control.”

In his opening remarks, Dr Marincowitz described how courtiers of Elizabeth I, including some who lived at St Albans, had petitioned the Queen for a charter to establish QE Boys.

She visited St Albans on several occasions when travelling between Hatfield and London and established a foundation there for a school.

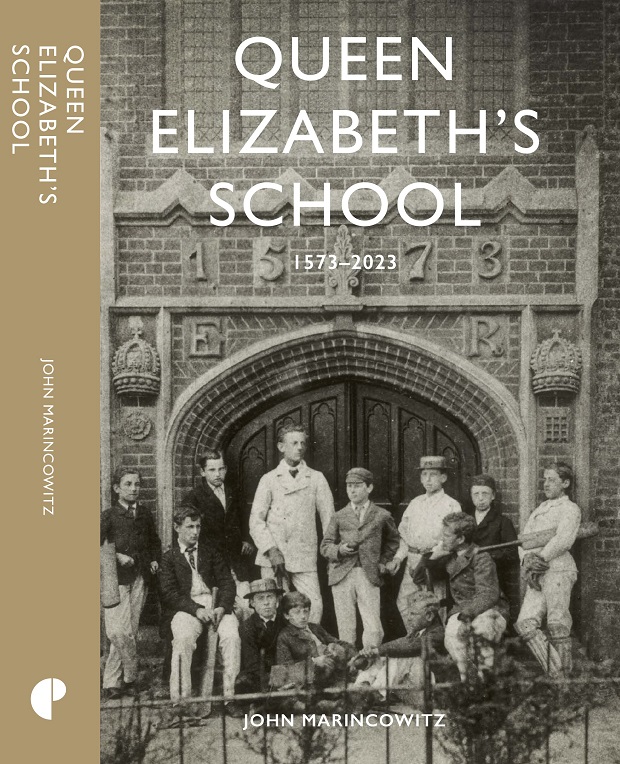

When QE was granted its charter in 1573, donations from church collections in the City of London helped to finance the construction of the original QE schoolhouse, now converted into the Tudor Hall, next to Barnet College.

Boys at the school would have ranged in age from six to 19, of whom 30 or so would have been days boys and 15 to 20 boarders who lodged in the roof space of the old school.

They would have come from families of the “middling sorts” – craftsmen, tradesmen, inn keepers, a few from professional families and some from the families of wealthy merchants.

All 50 boys would have attended prayers in the morning and at the end of the day; religious studies on Saturdays; and church services on Sunday.

They would have been split into seven groups – the top four forms would have been taught by the master, and younger boys by the usher.

They would have sat at wooden benches; learning would have been verbally based; and they would have spent a considerable amount of time in the classroom when compared with today. By 19 the boys would have been conversant in Latin, prepared to go to university.

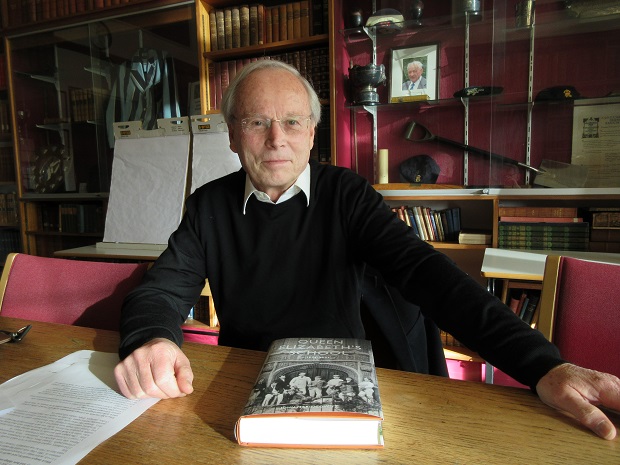

Dr Marincowitz, who was headmaster from 1999 to 2011, hopes readers will find that his book – Queen Elizabeth’s School 1573-2023 — provides a compelling account of what it was like to be at school in England over the last 450 years.

Historic archive material drawn from over 6,500 historical sources is available to see on the QE Collections website: https://www.qecollections.co.uk/

1 thought on “Looking back on 450 years education at QE Boys’ — former headmaster relives era of dramatic change”

Comments are closed.

‘3,500 applicants for 180 places’… What a sad state of affairs. Selective grammar schools such as QE boys are a blight on the education system.